How To Use Mpc 2000xl As Midi Controller

An Akai MPC60, the first MPC model | |

| Other names | MIDI Production Center, Music Production Controller |

|---|---|

| Classification | Music workstation |

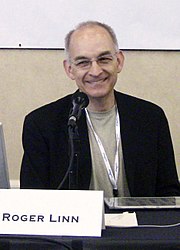

| Inventor(southward) | Roger Linn |

| Adult | 1988 |

The Akai MPC (originally MIDI Production Center, now Music Production Eye) is a series of music workstations produced past Akai from 1988 onwards. MPCs combine sampling and sequencing functions, allowing users to record portions of audio, change them and play them back as sequences.

The starting time MPCs were designed by Roger Linn, who had designed the successful LM-1 and LinnDrum pulsate machines in the 1980s. Linn aimed to create an intuitive instrument, with a grid of pads that tin can be played similarly to a traditional musical instrument such equally a keyboard or drum kit. Rhythms can be built not but from samples of percussion but samples of any recorded audio.

The MPC had a major influence on the development of electronic and hip hop music. It led to new sampling techniques, with users pushing its technical limits to creative effect. It had a democratizing consequence on music production, assuasive artists to create elaborate tracks without traditional instruments or recording studios. Its pad interface was adopted past numerous manufacturers and became standard in DJ engineering.

Notable users of the MPC include the American producer DJ Shadow, who used an MPC to create his influential 1996 anthology Endtroducing; the American producer J Dilla, who disabled its quantize feature to create signature "off-kilter" rhythms; and the rapper Kanye West, who used it to compose several of his best-known tracks. MPCs keep to be used in music, even with the appearance of digital audio workstations.

Evolution [edit]

By the late 1980s, drum machines had get popular for creating beats and loops without musicians, and hip hop artists were using samplers to have portions of existing recordings and create new compositions.[1] Grooveboxes, machines that combined these functions, such every bit those by Due east-mu Systems, required cognition of music product and cost up to $ten,000.[1]

The original MPC, the MPC-threescore, was a collaboration between the Japanese company Akai and the American engineer Roger Linn. Linn had designed the successful LM-1 and LinnDrum, two of the earliest drum machines to apply samples (prerecorded sounds).[2] His company Linn Electronics had closed post-obit the failure of the Linn 9000, a drum car and sampler. Co-ordinate to Linn, his collaboration with Akai "was a good fit because Akai needed a creative designer with ideas and I didn't want to do sales, marketing, finance or manufacturing, all of which Akai was very good at".[3]

Linn described the MPC as an attempt to "properly re-engineer" the Linn 9000.[3] He disliked reading education manuals and wanted to create an intuitive interface that simplified music production.[1] He designed the functions, including the panel layout and hardware specification, and created the software with his squad; he credited the circuitry to a team led past English engineer David Cockerell. Akai did the production engineering, making it "more than manufacturable".[three] The first model, the MPC60 (MIDI Production Eye), was released on December 8, 1988,[4] and retailed for $5,000.[1] It was followed by the MPC60 MkII and the MPC3000, and the MPC2000, which Linn did non piece of work on.[5]

After Akai went out of business in 2006,[6] Linn left the visitor and its assets were purchased by Numark.[7] Akai has continued to produce MPC models without Linn.[iii] Linn was critical, maxim: "Akai seems to be making slight changes to my quondam 1986 designs for the original MPC, basically rearranging the deck chairs on the Titanic."[7] [ dead link ]

Features [edit]

Instead of the switches and small-scale hard buttons of earlier devices, the MPC has a 4x4 grid of large pressure-sensitive rubber pads which can exist played similarly to a keyboard.[1] The interface was simpler than those of competing instruments; it can be used without a studio and connected to a normal sound system. Co-ordinate to Phonation , "nearly importantly, it wasn't an enormous, stationary mixing console with as many buttons every bit an airplane cockpit".[1]

Whereas artists had previously sampled long pieces of music, the MPC allowed them to sample smaller portions, assign them to split up pads, and trigger them independently, similarly to playing a traditional instrument such as a keyboard or drum kit.[1] Rhythms tin can be congenital not but from percussion samples but any recorded sound, such equally horns or synthesizers.[one]

The MPC60 only allows sample lengths of up to 13 seconds, as sampling memory was expensive at the fourth dimension and Linn expected users to sample short sounds to create rhythms; he did not anticipate that they would sample long loops.[7] Functions are selected and samples are edited with two knobs. Red "tape" and "overdub" buttons are used to save or loop beats.[1] The MPC60 has an LCD screen and came with floppy disks with sounds and instruments.[ane]

Legacy [edit]

DJ Shadow (pictured wearing an MPC shirt) created his landmark album Endtroducing with an MPC

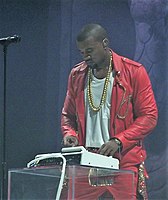

Kanye Due west performing with an MPC 2000XL

Linn predictable that users would sample short sounds, such as individual notes or pulsate hits, to use as building blocks for compositions. However, users began sampling longer passages of music.[8] In the words of Greg Milner, the author of Perfecting Sound Forever, musicians "didn't merely want the audio of John Bonham's kick pulsate, they wanted to loop and echo the whole of 'When the Levee Breaks'."[8] Linn said: "Information technology was a very pleasant surprise. Afterwards 60 years of recording, in that location are so many prerecorded examples to sample from. Why reinvent the wheel?"[8]

The MPC's ability to create percussion from whatever sound turned sampling into a new artform and allowed for new styles of music.[1] Its affordability and accessibility had a democratizing effect; musicians could create tracks on a unmarried machine without a studio or music theory knowledge, and it was inviting to musicians who did not play traditional instruments or had no music education.[1] [9] Musicians learnt how to button its technical limits; for example, the producer Om'Mas Keith would tape samples at high speeds, then slow them to their original pitch on the MPC, allowing him to tape samples longer than the MPC's maximum.[i]

Co-ordinate to Vox, "The explosion of electronic music and hip hop could non have happened without a machine equally intimately connected to the creative process every bit the MPC. It challenged the notion of what a ring tin look like, or what it takes to be a successful musician. No longer does i need five capable musicians and instruments."[ane] MPCs proceed to be used in music, even with the advent of digital audio workstations, and fetch high prices on the used market place.[ane] The 4x4 filigree of pads was adopted by numerous manufacturers and became standard in DJ technology.[ane]

Engadget wrote that the bear upon of the MPC on hip hop "cannot exist overstated".[9] The British rapper Jehst saw it every bit the next step in hip hop evolution subsequently the introduction of the TR-808, TR-909 and DMX drum machines in the 1980s.[10] The American producer DJ Shadow used an MPC60 to create his influential 1996 album Endtroducing, which is composed entirely of samples.[11] The American producer J Dilla disabled the quantize feature on his MPC to create his signature "off-kilter" sampling style.[12] After his expiry, his MPC was preserved in the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture in 2014.[13] [14] The rapper Kanye West used the MPC to compose several of his best-known tracks and much of his breakthrough album The Higher Dropout; [one] W airtight the 2010 MTV Video Music Awards with a performance of his 2010 runway "Runaway" on an MPC.[15]

See also [edit]

- Akai

- Drum machine

- Groovebox

- Sampler

References [edit]

- ^ a b c d eastward f chiliad h i j thousand fifty m northward o p q Aciman, Alexander (sixteen April 2018). "Meet the unassuming drum car that changed music forever". Vox . Retrieved xi May 2018.

- ^ McNamee, David (22 June 2009). "Hey, what's that sound: Linn LM-1 Drum Computer and the Oberheim DMX". the Guardian . Retrieved nine February 2018.

- ^ a b c d "Feature: Industry Interview -Roger Linn @ SonicState.com". sonicstate.com . Retrieved 13 May 2018.

- ^ Solida, Scott (24 Jan 2011). "The 10 most important hardware samplers in history". MusicRadar . Retrieved thirteen May 2018.

- ^ White, Paul (June 2002). "The return of Roger Linn". Sound on Audio . Retrieved 16 December 2018.

- ^ "Akai Professional MI launches bankruptcy proceedings". kanalog.jp. Archived from the original on 12 January 2006. Retrieved 7 December 2005.

- ^ a b c "INTERVIEW with Roger Linn". BBOY TECH REPORT. 2 November 2012. Retrieved 13 May 2018.

- ^ a b c Milner, Greg (3 November 2011). Perfecting Sound Forever: The Story of Recorded Music. Granta Publications. ISBN9781847086051. Archived from the original on nine December 2018. Retrieved vii December 2018.

- ^ a b Trew, J. (22 Jan 2017). "Hip-hop's nearly influential sampler gets a 2017 reboot". Engadget . Retrieved 3 April 2018.

- ^ "My Precious: The History of The Akai MPC". Clash Magazine . Retrieved three Apr 2018.

- ^ "DJ Shadow". Keyboard. New York. October 1997. Archived from the original on 23 February 2013. Retrieved xvi March 2013.

- ^ Helfet, Gabriela (ix September 2020). "Drunk drummer-style grooves". Attack Magazine . Retrieved 24 January 2022.

- ^ Aciman, Alexander (16 April 2018). "Meet the unassuming drum machine that changed music forever". Voice . Retrieved 23 January 2022.

- ^ Military camp, Zoe (19 July 2014). "J Dilla equipment volition be donated to Smithsonian Museum". Pitchfork . Retrieved 23 January 2022.

- ^ Caramanica, Jon (13 February 2011). "Lots of Beats No Drums in Sight". The New York Times. New York.

Farther reading [edit]

- "Akai MPC2000". Future Music. No. 56. Future Publishing. May 1997. p. 39. ISSN 0967-0378. OCLC 1032779031.

External links [edit]

- Official Roger Linn site

How To Use Mpc 2000xl As Midi Controller,

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Akai_MPC

Posted by: smithbispecephe.blogspot.com

0 Response to "How To Use Mpc 2000xl As Midi Controller"

Post a Comment